Two narratives dominate today’s debate about the future of work: “robots will replace everyone” and “technology will unlock an ocean of new professions.” Both rely on neat cost curves, while the real economy stays stubbornly down‑to‑earth. This essay offers five field stories that explain why companies still pay humans even for tasks that look eminently automatable.

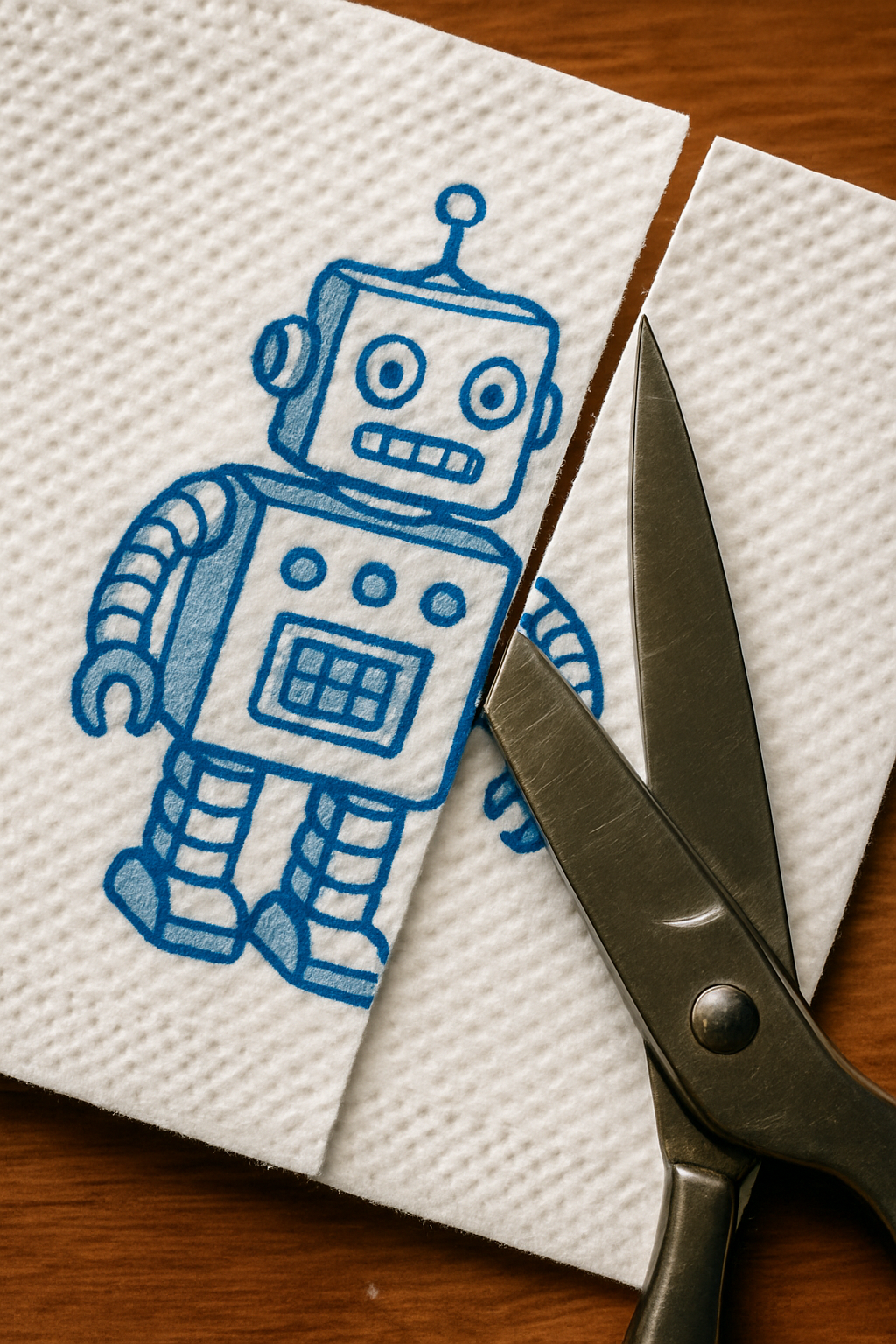

Story 1. Quartered napkins

A large industrial group saw its like‑for‑like sales plunge more than 40 % year‑on‑year. Instead of chasing new markets, management launched a savings drive: hiring freeze, R&D portfolio cuts, support‑budget trims.

We met the client team in their corporate cafeteria. Each table had a napkin dispenser. Grabbing a sheet, I realized it was only a quarter of a napkin: the edge showed ragged scissor marks. The administrator explained the canteen is subsidized, so staff manually cuts napkins to buy them less often.

This is what I call the napkin effect. It shows up whenever one hour of human labor is cheaper than paper napkins. In the industry we sometimes nickname it somewhat cynically “protein automation”: swapping expensive code and silicon for low‑paid human.

Story 2. Mining and wage arithmetic

During a chat with the IT architect of a Russian mining corporation, I noted they employ five times more people per ton of output than a European rival. The response was blunt: “With our wages we could double headcount again and margins would stay intact.” Cheap labour plus high commodity prices push the automation payback years into the future. Robots remain a glossy slide deck, not a P&L reality.

Story 3. Automated recruiting vs. live head‑hunting

A national retail chain rolled out a digital “hiring factory” for store staff and laid off its recruiters. Speed and formal accuracy improved. A competitor, who kept its human recruiters, exploited the gap: using cheap OSINT (discarded receipts near shop exits are enough to gauge turnover), recruiters walked into high‑performing stores during business hours and offered managers a job switch with a 10 % salary bump. One firm’s automation became the other’s talent pipeline.

Story 4. Robotaxis, driverless trucks and… train drivers

Robotaxis

Driver wages are the biggest cost item in taxi economics. Remove the human and profits should soar. Yet lidars, cameras, compute units plus map‑making, cybersecurity and incident‑response teams still cost more. Demand is lumpy, so autonomous cars may idle as much as conventional ones. Projects like Waymo and Cruise are impressive, but their cost per mile remains above the classic model.

Driverless trucks

Highway logistics shows similar math: capital for R&D, infrastructure and new competencies still outweighs savings on truckers’ wages. Only a mass sensor price collapse and a major road upgrade can flip the equation.

Why trains still have drivers

The first automatic‑train‑operation project dates to the 1920s, and Japan and Europe ran major pilot lines in the 1980s. Track guidance looks easier than road traffic, yet full de‑crewing requires network‑wide signaling overhaul and remote emergency handling. The total cost of ownership still outweighs savings on locomotive crews, so most trains keep human drivers.

Story 5. Where automation does pay off

Contact centers often move tier‑1 support to AI models and overall spend genuinely drops. The price is vendor lock‑in: once addicted to a proprietary model, the company is hostage to tariff hikes or may end up competing with the vendor should it vertically integrate the same service.

“Napkins” at macroeconomy scale

In the late 20th century, manufacturers from the US and Europe relocated plants to low‑wage, lightly regulated regions. A similar shift hit services: e‑commerce, ride‑hailing and food delivery ballooned a class of migrant couriers and drivers. Industries became “digital,” yet the headcount in low‑paid roles grew.

Robotization is not always a tragedy

Let’s kill some of that eschatological joy with a bit of history. Japan’s experience shows robots don’t inevitably destroy jobs. According to Robots and Employment: Evidence from Japan, 1978–2017, adding one industrial robot per 1,000 workers correlated with a 2.2 % increase in employment as people moved to higher‑value tasks.

Takeaways for your next important meeting

- As long as the total cost of automation (CapEx, development, maintenance, vendor dependency) exceeds wages, business rationally reaches for the scissors.

- Once labor gets pricier or technology cheaper, the curves cross – automation hurts laggards’ profits first.

- To survive the crossover, be either more valuable than the machine or cheaper than its ownership. The former is usually more fun.

EBITDA is still the lighthouse metric: before branding a service “digital,” make sure the robot is well aligned with your business model and actually outperforms the person with scissors on total cost of ownership.

PS

Recently I’ve been job-hunting. At some point I realized I should also look at consulting vacancies. Guess where the Big Four and other major firms are posting the bulk of UX and Service Design openings right now? It seems to be India. If that’s not the napkin effect, what is?