Over the past few weeks, I’ve written and published five case studies about the most exciting projects from my career as a service designer. I believe this is sufficient for a portfolio; hiring managers rarely explore even this much.

Now, I’d like to breathe life into this space by sharing more personal, less structured posts. Let’s start with usability.

Usability: Comfort or a Hidden Trap?

I often hear that service design is about usability. But what do we really mean by usability? In this context, it’s like a comfy chair or your favorite slippers.

Service design is 80% research and 20% designing based on research data. It’s about understanding the value and creating a relevant value proposition.

Let me explain with the example of one product I wrote about in my Portfolio.

The company I worked with has been around for 25 years and, over time, accumulated hundreds of internal services from various departments: HR, IT, office management, and others. Some services are centralized in the headquarters or shared services centers, while others are localized across dozens of geographically distributed branches. Most services are requested through various channels: corporate email, phone calls, text messages to the responsible parties, etc. The most developed service function—IT—receives less than 1.5% of requests via the service portal. At the start of the research, some services were so well-hidden that users only discovered them through the research itself.

The challenge was to create a unified service window, eliminate familiar but inefficient channels, and maintain service quality throughout the transition.

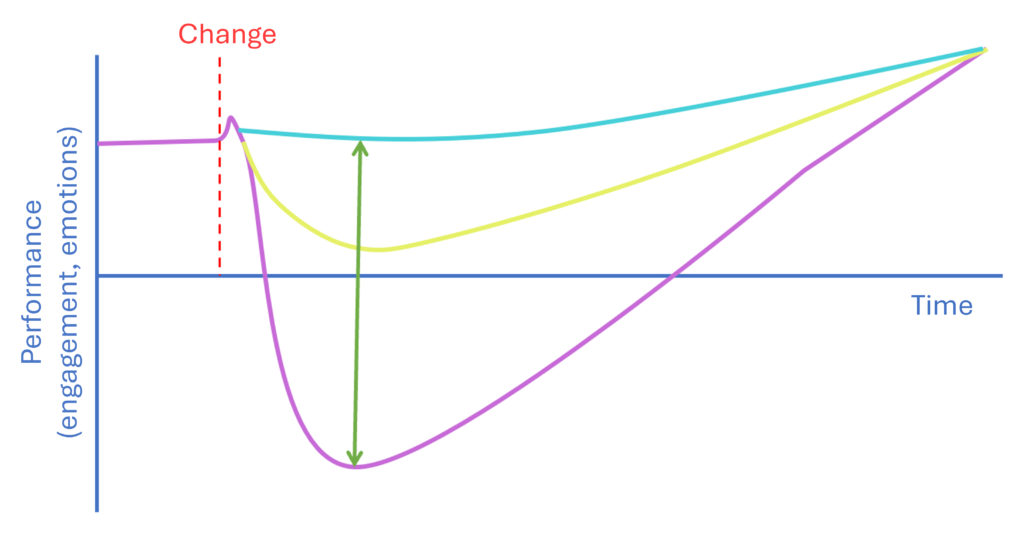

Management theory teaches that any change leads to a dip in productivity due to factors like reduced engagement and increased cognitive load (the purple curve). Change management helps smooth out this curve (the yellow curve). In our case, applying service design tools allowed us to eliminate this dip altogether (the turquoise curve).

Breaking the Barrier of “Comfort”

In any routine process, there are implicit barriers and irritants. Users become so accustomed to them that they no longer feel their impact—whether it’s excessive effort, time loss, or negative emotions. It feels comfortable. But like the chair that harms your posture or slippers that wear unevenly, it may be causing harm without the user even realizing it.

User research helped us uncover these issues and made addressing them the foundation of our design.

We discovered what could truly help users and built a relevant value proposition. By providing the product with a quality search function and an intuitive catalog, we reduced the time spent finding services and submitting requests significantly. We made the product both beautiful and light, eliminating the need for users to provide extra information, engage in correspondence with service providers, and handle approvals on their own. We started informing and proactively updating users.

Before, during, and after the change, we measured user satisfaction. It turned out that after the switch to the unified service window, satisfaction not only remained stable but actually increased by several tenths of a point (from 4.65/5 to 4.93/5).

Why is it important not to rely on comfort?

Because many problems exist from the start and become such a part of the user’s experience that they no longer even notice them. They’ve accepted them as part of their “normal.” But these problems are still barriers to a truly efficient experience.

One of the commandments of service design states: “People think one thing, say another, do a third, think they’re doing a fourth, and say they’re doing and thinking a fifth.”

A well-designed research approach helps uncover the true nature of these problems, and it’s on this foundation that a value proposition is built. This is what makes a product successful: ingrained, in demand, pleasant, and, finally, truly usable. A tool that genuinely helps people.